Iran Paid for Su-35 Jets, But Russia Won’t Deliver Them

Earlier this month, Brigadier General Hamid Vahedi, Iran’s air force commander, ended weeks of speculation about the imminent delivery Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets.

Earlier this month, Brigadier General Hamid Vahedi, Iran’s air force commander, ended weeks of speculation about the imminent delivery Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets. “Regarding the purchase of Su-35 fighter jets [from Russia], we need them, but we do not know when they will be added to our squadron. This is related to the decision of [Iran’s] high-ranking officials,” he stated in an interview on state TV.

Vahedi's comments sparked speculation about dysfunction in the Russia-Iran partnership, including that Israel had successfully convinced Russia to postpone delivery of the advanced fighter jets to Iran.

While officials in Tehran continue to pursue a partnership with Russia, it is increasingly clear that Russian officials see their relationship with Iran as little more than a card that can be played according to their needs.

Russia’s potential sale of Su-35 jets to Iran has been connected to the deeper military cooperation between the two countries since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Iranian drones are being used by Russian forces to bomb Ukrainian cities. The first drones were transferred from Iran to Russia around one year ago.

But Iran has been waiting for far more than a year to receive the Su-35, which would prove a major upgrade in capabilities for Iran’s aging air force, largely comprised of American jets in service since before the 1979 revolution.

According to one current and one former diplomat with direct knowledge of the matter, Iran made “full payment” for 50 Su-35 fighter jets during the second term of President Hassan Rouhani. The officials requested anonymity given the sensitivity of Iran’s arms purchases. According to the former diplomat, at the time of purchase Russia had promised to deliver the Su-35s in 2023. Neither source expects that the deliveries will be made this year.

A third source, a security official, speaking on background, expressed disappointment that Vahedi’s “uncoordinated interview” had called attention to the fact that the deliveries were now in doubt. Iranian officials feel embarrassment over Russia’s failure to adhere to commitments.

The delay in the delivery could be traced to the strong relationship between Russia and Israel. In June, Axios reported that Israeli officials confronted Russian counterparts over Russia’s growing military cooperation with Iran and the possibility of Russia providing Iran advanced weapon systems. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu disclosed the “open and frank” dialogue with Russian officials in a closed-door hearing with Israeli lawmakers on June 13.

In the view of the former diplomat, due to their arrogance, Iranian hardliners “fell into the trap” of believing that they were an equal partner to Russia, simply because “the Russians are queuing up to buy arms from them.”

The drone transfers have contributed to Iran’s political isolation, giving Western officials the impression of deepening cooperation between Russia and Iran, even as the Iranian Foreign Ministry continues to claim that Iran remains a neutral party in the Ukraine war. According to the security official, neutrality remains the consensus position of the Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, but he warned that country’s military brass may not all share that same view.

Notwithstanding the ambitions of Iranian generals, Russia continues to treat Iran far worse than an ally. Earlier this week, Russia issued a joint statement with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), affirming the United Arab Emirate’s claims on three Iranian islands: the Greater Tunb, the Lesser Tunb, and Abu Musa. The statement enraged Iranian officials. Ali Akbar Velayati, a senior advisor to Iran’s Supreme Leader, called Russia’s assent to the statement “a move borne of naivety.” Iran’s foreign minister and its government spokesperson stressed in statements that Iran will not tolerate claims on the three islands from any party. The officials had made such statements before—a China-GCC joint statement from December 2022 caused a similar public outcry.

As Iranian officials are forced to defend their ties with Russia once again, a question remains. Why does Iran have so little leverage over Russia, even after the Russian invasion of Ukraine? The answer lies in the mindset of Iranian officials.

Back in May, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamanei, declared that “Dignity in foreign policy means saying no to the diplomacy of begging.” The slogan “diplomacy of begging” has become popular among conservatives and the hardliners, who have used it to condemn the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and to accuse former Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif of begging the West for sanctions relief. But if begging the West for sanctions relief is wrong, why are hardliners eager to beg Russia for the Sukhoi jets?

Tehran’s ties with Moscow were never built on trust. They were built on mutual fears and mutual needs. Were the administration of President Ebrahim Raisi to realize that looking to the West does not preclude political and economic relations with Russia and China, Iran could strengthen its position in the Middle East and regain leverage in its relationship with Russia. Until then, the Russians will continue to look at their relationship with Iran as a nothing more than playing card.

Photo: Wikicommons

Sanctions, CBDCs, and the Role of ‘Decentral Banks’ in Bretton Woods III

In a world with two parallel financial systems, a country would not necessarily have a single reserve bank.

In a recent conversation on the Odd Lots podcast, Zoltan Pozsar offered an interesting use case for central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), a potentially transformative technology that 86 percent of central banks are “actively researching” according to a BIS survey from 2021.

Pozsar, a former Credit Suisse strategist who is setting up his own research outfit, believes that a new global monetary order is emerging—he calls it “Bretton Woods III.” As part of this order, the adoption of CBDCs will enable central banks to play a more pivotal role in global trade through the formation of a “state-to-state” network that is intended to be independent of Western financial centres and the dollar. In this network, central banks will play a “dealer” role when it comes to providing liquidity for trade among developing economies. Commenting on China’s push to internationalise the renminbi, Pozsar set out his vision:

You need to imagine a world where five, ten years from now we are going to have a renminbi that’s far more internationally used than today, but the settlement of international renminbi transactions are going to happen on the balance sheets of central banks. So instead of having a network of correspondent banks, we should be thinking about a network of correspondent central banks and a world where you have a number of different countries and in which each of those different countries have their banking systems using the local currency but when country A wants to trade with country B… The [foreign exchange] needs of those two local banking systems are going to be met by dealings between two central banks.

In short, Pozsar believes that the adoption of CBDCs will enable the creation of a “new correspondent banking system” built around central banks. But even if central banks do begin to use CBDCs to settle trade, reducing dependence on dollar liquidity and legacy correspondent banking channels, the underlying problem motivating CBDC adoption will remain.

Moving away from the dollar-based financial system is foremost about geopolitics. Globalisation, as we have known it, reinforced a unipolar order. The United States was able to leverage its unique position in the global economy into unrivalled superpower status. In the last two decades, the weaponisation of the dollar further augmented U.S. power—Americans are uniquely able to wage war without expending military resources, which is another kind of exorbitant privilege. As Pozsar notes, the countries moving fastest towards CBDCs are those that are either currently under a major U.S. sanctions program (Russia, Iran, Venezuela etc.) or at risk of being targeted (China, Pakistan, South Africa etc.) These countries recognise “that it is pointless to internationalise your currency through a Western financial system… and through the balance sheets of Western financial institutions when you basically do not control that network of institutions that your currency is running through.” As Edoardo Saravalle has argued, the power of U.S. sanctions is actually underpinned by the central role of the Federal Reserve in the global economy.

Adopting CBDCs would enable countries to reduce the proportion of their foreign exchange reserves held in dollars while also reducing reliance on U.S. banks and co-opted institutions such as SWIFT to settle cross-border payments. However, even if countries reduce their exposure to the dollar-based financial system in this way, U.S. authorities will still be able to use secondary sanctions to block central banks from the U.S. financial system for any transaction with a sanctioned sector, entity, or individual. Any financial institution still transacting with a designated central bank could likewise find itself designated.

Moreover, even if Bretton Woods III emerges, leading to the formation of a robust parallel financial system that is not based on the dollar, central banks will continue to engage with the legacy dollar-based financial system. It is difficult to image a central bank correspondent banking network in which nodes are not shared between the dollar-based and non-dollar based financial networks. As such, the threat of secondary sanctions or being placed on the FATF blacklist—moves that would cut a central banks access to key dollar-based facilities—will remain a significant threat.

Even Iran, which is under the strictest financial sanctions in the world, including multiple designations of its central bank, continues to depend on dollar liquidity provided through a special financial channel in Iraq. A significant portion of Iran’s imports of agricultural commodities continue to be purchased in dollars. Iran earns Iraqi dinars for exports of natural gas and electricity to its neighbour. The Iraqi dinars accrue at an account held at the Trade Bank of Iraq. The dinar is not useful for international trade, and so Iran converts its dinar-denominated reserves into dollars to purchase agricultural commodities—a waiver issued by the U.S. Department of State permits these transactions. The dollar liquidity is provided by J.P. Morgan, which plays a key role in the Trade Bank of Iraq’s global operations, having led the creation of the bank after the 2003 invasion.

The fact that the most sanctioned economy in the world depends on dollar liquidity for its most essential trade suggests that central banks will remain subject to U.S. economic coercion, owing to continued use of the dollar for at least some trade. But even in cases where Iran conducts trade without settling through the dollar, U.S. secondary sanctions loom large.

For over a decade, China has continued to purchase large volumes of Iranian oil in violation of U.S. sanctions, paying for the imports in renminbi. Iran is happy to accrue renminbi reserves because of its demand for Chinese manufactures. But owing to sanctions on Iran’s financial sector, Iranian banks have struggled to maintain correspondent banking relationships with Chinese counterparts. When the bottlenecks first emerged more than a decade ago, China tapped a little-known institution called Bank of Kunlun to be the policy bank for China-Iran trade.

The bank was eventually designated by the US Treasury Department in 2012. Since then, Bank of Kunlun has had no financial dealings with the United States, but that has not eased the bank’s transactions with Iran. Bank of Kunlun is owned by Chinese energy giant CNPC, an organisation with significant reliance on U.S. capital markets. When the Trump administration reimposed secondary sanctions on Iran in 2018, Bank of Kunlun informed its Iranian correspondents that it would only process payment orders or letters of trade in “humanitarian and non-sanctioned goods and services,” a move that was intended to forestall further pressure on CNPC. Ultimately, Bank of Kunlun had far less exposure to the U.S. financial system that China’s own central bank ever will, a fact that points to the limits of a central bank correspondent banking network. For CBDCs to serve as a defence against the weaponised dollar, they would need to be deployed by institutions that maintain no nexus with the dollar-based financial system. It is necessary to think beyond central banks.

What Pozsar has failed to consider is that in a world with two parallel financial systems, a country would not necessarily have a single reserve bank. Alongside central banks, we can envision the rise of what I call decentral banks. If a central bank is a monetary authority that is dependent on the dollar-backed financial system and settles foreign exchange transactions through the dollar, a decentral bank is a parallel authority that steers clear of the dollar-backed financial system and settles foreign exchange transactions through CBDCs. The extent to which Bretton Woods III really represents the emergence of a new bifurcated global monetary order depends not only on the adoption of CBDCs, but also the degree to which the innovations inherent in CBDCs enable countries to operate two or more reserve banks whose assets and liabilities are included in a consolidated sovereign balance sheet.

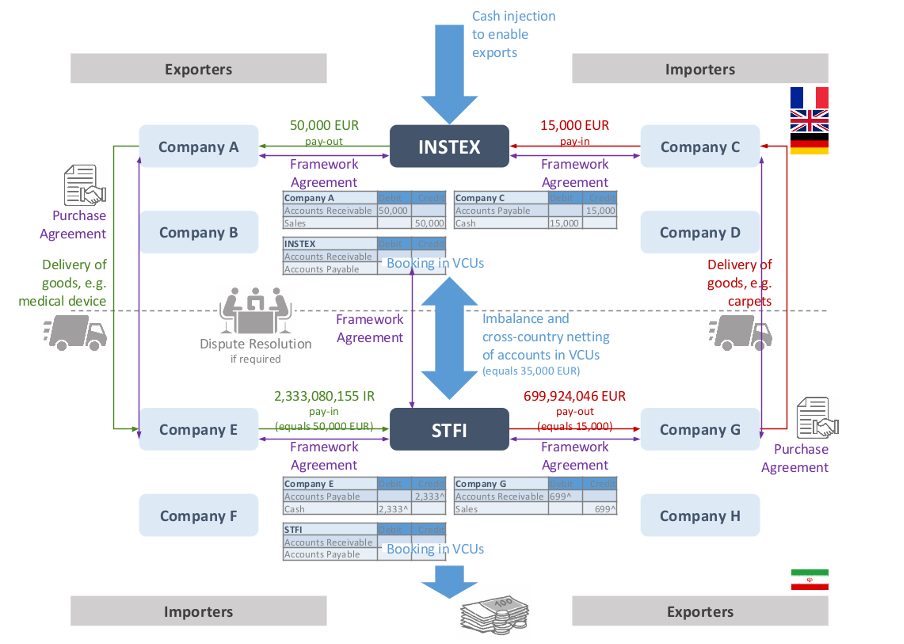

Again, Iran offers an interesting case study for what this innovation might look like. The reimposition of U.S. secondary sanctions on Iran in 2018 crippled bilateral trade between Europe and Iran. Conducting cross-border financial transactions was incredibly difficult owing to limited foreign exchange liquidity and the dependence on just a handful of correspondent banking relationships. France, Germany, and the United Kingdom took the step to establish INSTEX. As a state-owned company, INSTEX would work with its Iranian counterpart, STFI, to establish a new clearing mechanism for humanitarian and sanctions-exempt trade between Europe and Iran. The image below is taken from a 2019 presentation used by the management of INSTEX to explain how trade could be facilitated without cross-border financial transactions.

The model is strikingly like Pozsar’s suggestion that CBDCs will enable central banks to settle trades using their balance sheets, rather than relying on the liquidity of banks and correspondent banking relationships. INSTEX and STFI were supposed to net payments made by Iranian importers to European exporters with payments made by European importers to Iranian exporters, using a “virtual currency unit” to book the trade. The likely imbalances would be covered by a cash injection into INSTEX (Europe was exporting far more than it was importing after ending purchases of Iranian oil). It was an elegant solution, which sought to scale-up the methods being used by treasury managers at multinational companies operating in Iran to purchase inputs and repatriate profits.

Earlier this year, INSTEX was dissolved. Its shareholders, which eventually counted ten European states, lacked the political fortitude to see the project through. Notwithstanding bold claims about preserving European economic sovereignty in the face of unilateral American sanctions, there was always a sense among European officials that Iran was undeserving of a special purpose vehicle. But as the world moves to a new financial order, more institutions like INSTEX will emerge. Pozsar’s vision is bold insofar as he believes central banks will establish new cross-border clearing mechanisms based on CBDCs. But if new digital currencies can emerge to displace the dollar in the global monetary order, so too can new institutions be established.

Pozsar’s vision for Bretton Woods III becomes more convincing if one considers that the emergence of institutions such as decentral banks could lead to the creation of correspondent banking networks that are truly divorced from the dollar-based financial order. However, there remain plenty of reasons to doubt that such a system will emerge. Pozsar appears to have given little consideration to the issue of state capacity. Most countries have poorly managed central banks as it is—in the Odd Lots interview he pointed to Iran and Zimbabwe as early movers on CBDCs. We should have low expectations for the ability of most governments to develop and implement new technologies such as CBDCs or to establish wholly new institutions such as decentral banks. Moreover, the ability of the U.S. to use carrots and sticks to interfere with those efforts should not be underestimated.

There may be compelling structural drivers for something like Bretton Woods III, namely the rise of China and the overall shift in the global distribution of output. But somewhere along the way those structural drivers need to be converted into institutional processes. Bretton Woods is shorthand for the idea that monetary rules are as important for the operation of the global economy as the macroeconomic fundamentals. Countries reluctant to break the rules will struggle to rewrite them.

Photo: Canva

When it Comes to Middle East Diplomacy, Chinese and European Interests Align

In March, China managed to a broker a détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia, achieving a diplomatic breakthrough that had eluded European governments. But Europe and China have shared interests in the region and there is scope for the two powers to work together to foster further multilateral diplomacy.

A version of this article was originally published in French in Le Monde.

In March, China managed to a broker a détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia, achieving a diplomatic breakthrough that had eluded European governments. But Europe and China have shared interests in the region and there is scope for the two powers to work together to foster further multilateral diplomacy.

Europe and China, which both depend on energy exports from the Persian Gulf, have long relied on the US-led security architecture in the region. But the 2019 attacks on oil tankers in the UAE and oil installations in Saudi Arabia, widely attributed to Iran, were a watershed moment. Shifting US interests and President Trump’s erratic reaction to those attacks forced the Chinese and Europeans to take more responsibility for regional security over the last four years.

In 2020, China presented its idea for regional security in the Persian Gulf, arguing that with a multilateral effort, the Persian Gulf region can become “an oasis of security.” In the time since, the agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, signed in March, can be considered an outcome of such efforts.

European governments have also sought to back multilateral diplomacy. France was intent on creating a platform for Tehran and Riyadh to engage in dialogue. President Macron helped launch the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership that was held in August 2021. The conference was a unique opportunity to gather countries that had not sat around the same table for years. Officials from Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, in addition to Egypt, Jordan, Turkey, and France participated. Oman and Bahrain joined the second gathering which took place last December in Amman, Jordan.

The European Union also expressed its support for the Baghdad process. Joseph Borrell said during the Second meeting that “promoting peace and stability in the wider Gulf region… are key priorities for the EU.” Adding that “we stand ready to engage with all actors in the region in a gradual and inclusive approach.”

The Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council on a strategic partnership with the Gulf reflects the EU’s keenness on expanding its engagements with the region, particularly on economic ties. The partnership is focused on the GCC, but it mentions that “involvement of other key Gulf countries in the partnership may also be considered as relations develop and mature”—a reference to Iran and Iraq.

Clearly, China and the European Union have multiple areas of mutual concern in the Persian Gulf region. Ensuring freedom of navigation, the undisrupted flow of oil and gas from the region, and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons are shared priorities. But while China is now a central player in the strategic calculations of all states in the region, the Europeans are being largely left out.

European diplomatic outreach has faltered in the face of new political pressures arising from Iran’s continued nuclear escalations, its involvement in Russia’s war against Ukraine, and its repression of ongoing protests for democratic change.

The French president was coincidently in China when the Beijing Agreement was signed, and he welcomed the rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Given shared interests, European officials must now find ways to engage with Chinese counterparts on fostering greater regional diplomacy in the Persian Gulf.

There are reports that a regional summit will take place in Beijing later this year, involving all GCC states, Iran and Iraq. This is an important opportunity for multilateral dialogue and cooperation. European governments should consult with regional players and China to secure a seat at the meeting. The EU can help regional countries find ways to jointly tackle basic issues that have impeded economic growth which have resulted in spillover effects such as increased food insecurity and inability to mitigate the rising challenges of climate change.

In parallel, the Baghdad Conference could emerge as an EU-backed platform for economic cooperation in tandem to the now ongoing political and security dialogue process in China. The EU can draw in regional countries to help with reconstruction efforts in Iraq, a country that is in dire need of foreign investment. Given the shuttle diplomacy conducted by Iraqi officials between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and considering the role of France and the EU in the Baghdad conference, it would be apt to explore EU-supported joint economic projects in Iraq, especially those projects that create mutual economic interests between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Whether in Baghdad, Amman, or Beijing, inclusive regional gatherings are needed to address common economic challenges facing all eight countries surrounding the Persian Gulf. Europe can make significant contributions towards regional dialogue on economic integration by helping to create multilateral platforms, transfer knowhow and technology, and provide financial support. These are areas where China has significantly increased its activities, but European countries enjoy far greater experience in establishing the institutions and infrastructure needed for regional economic development. European officials can leverage this experience to support regional diplomacy. Such efforts would also cement European regional influence at a time when US influence may be waning.

The newly appointed EU Special Representative for Gulf Affairs, Luigi Di Maio, should directly oversee and coordinate initiatives in support of economic diplomacy and integration in the region, finding common ground with China to head off competition. Achieving security through stronger diplomacy and deeper economic ties represents a transformative goal that the region can rally around.

Photo: IRNA

SIPRI Has Revised Four Years of Data on Iran's Military Spending

SIPRI has corrected its data on Iran’s military spending, applying a more relevant exchange rate for dollar conversions. Instead of ranking as the 14th largest military spender in the world in 2021, Iran was actually ranked 39th.

SIPRI—the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute—has just published its “Yearbook” for 2022. The flagship annual publication offers civilian and military leaders around the world a way to compare military spending between countries and to gauge which countries are investing in greater military power.

Last year, I identified a major problem with the data about Iran’s military spending. The 2021 Yearbook estimated Iran’s military spending at $24.6 billion, a total that put it just above Israel in the rankings, as the 14th largest military spender in the world. This did not make sense.

Iran’s military, while posing a threat within the region, does so primarily because of inexpensive missile and drone systems and heavy reliance on proxy forces. Iran’s military lacks the kinds of advanced aircraft, armour, and other systems that are typically found in the arsenals of the world’s top military spenders.

A closer examination of the SIPRI data, and communication with SIPRI’s researchers, revealed that the Swedish think tank had been using the wrong exchange rate to convert Iran’s local currency military expenditures into dollar values. The researchers were using the “official” central bank exchange rate, which has for several years been a subsidised exchange rate used exclusively for the import of essential goods.

This common mistake has been rectified. SIPRI researchers note in the 2022 Yearbook dataset that they are using the NIMA exchange rate to convert to dollars, which results in a far better estimate of the Iranian state’s true purchasing power. The historical data has been corrected going back to 2018.

The impact of the correction is significant. The revised figures mean that instead of ranking as the 14th largest military spender in the world in 2021, Iran was actually ranked 39th. In 2022, spending totalled $6.8 billion. That is a mere fraction of the military spending of regional rival Saudi Arabia, which spends an estimated $75 billion. Iran even spends less on its military than regional minnow Kuwait.

SIPRI should be commended for making this correction. But in certain respects, the damage has been done. For several years their data was used to suggest that Iran posed a much greater threat to regional and global security than it truly did. A significant number of authoritative publications and news reports relied upon the SIPRI data to put Iran’s military spending in context and unfortunately used the inflated dollar totals published between 2018 and 2021. Those inflated figures conformed to a pervasive and convenient narrative—this may explain why the issue went unresolved for so long.

Photo: IRNA

Are Sanctions Boosting Corporate Profits in Iran?

Iranian listed companies have managed to grow profits despite major cost pressures stemming from sanctions. This may be because firms are exercising extraordinary pricing power.

Last year I wrote a major report examining how the inflation generated by sanctions hurts households in Iran. In the report, I note evidence of “the increased cost of inputs being passed on to consumers.” In other words, citing anecdotal evidence, I suggested that Iranian firms were raising prices to protect their margins and that this was contributing to inflation. But the report lacked a substantive review of how firms react to the pressures created by financial and sectoral sanctions.

Firm behaviour under sanctions is understudied. The widespread assumption is that sanctions are bad for business. After all, they create significant dysfunction in the targeted economy. But the firm-level evidence is mixed. Sanctions do not tend to drive firms out of business, suggesting that companies find ways to adjust to the obvious cost pressures. Hadi Esfahani’s firm-level research has shown that “exits” (companies going out of business) played only a small role in changes in output, employment, and exports following the imposition of financial and sectoral sanctions in Iran in 2012. Saeed Ghasseminejad and Mohammad Jahan-Parvar’s study of Iranian companies listed on the Tehran Stock Exchange between 2011 and 2016 provides evidence that sanctions negatively impact profitability, but even sanctioned firms remained profitable in the period of their study. The profitability of firms that were subject to sectoral sanctions fell from an average of 16 percent to 11 percent—the margins remained healthy.

But what are the processes that are enabling Iranian firms to adjust to sanctions? A potential answer can be found in a new paper by Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner titled “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why Can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?” Using data on the profit margins of major US companies in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic, Weber and Wasner examine how firms “exercise pricing power to enhance or protect short-run profitability” in the face of acute cost pressures.

While the new research by Weber and Wasner does not discuss sanctioned economies, they describe conditions that can also be observed in Iran. Sanctions represent first and foremost a change in the supply environment—an emergency characterised by surging input costs. Financial and sectoral sanctions force most foreign companies to cease supplying customers in the targeted economy. But even when inputs remain available, currency devaluation triggered by the impact of sanctions on foreign exchange revenue and the accessibility of reserves makes those inputs more expensive. As a result, firms in the targeted country face supply chain bottlenecks and significant cost pressures. Purchasing managers’ index data from Iran makes clear that high producer prices and difficulties maintaining raw material and machinery inventories are the most persistent challenge facing Iranian manufacturing firms.

Moreover, the processes that Weber and Wasner believe underpin the “sellers’ inflation” that occurred after the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States are also at play in Iran. First, “sector-wide cost increases” lead to an “implicit agreement” among firms to raise prices. This occurs because “all firms want to protect their profit margins and know that the other firms pursue the same goal.” While state firms do dominate some sectors of Iran’s economy, such as the automotive industry, the broader manufacturing sector is dominated by private sector firms and is generally unconsolidated. The price increases seen in Iran reflect such implicit agreements and not price leadership by a few dominant firms.

Second, Weber and Wasner argue that “bottlenecks can create temporary monopoly power which can even render it safe to hike prices not only to protect but to increase profits.” In Iran, bottlenecks arose due to the effects of sanctions on imports. Under sanctions, domestic manufacturers face less competition from imported goods and the same bottlenecks also make it difficult to ramp-up output. Given the production constraints, it is nearly impossible for firms to grab market share by undercutting the competition and boosting sales. Because firms will not substantially sacrifice sales by raising prices, they can be understood to enjoy a kind of monopoly power.

Third, much like how the ongoing pandemic disruptions legitimise “price hikes and create acceptance on the part of consumers to pay higher prices,” so too do sanctions help render demand less elastic. Iranian consumers have come to understand high rates of inflation as the outcome the American sanctions and their own government’s monetary policy. While there has been some scrutiny of predatory pricing by Iranian firms in recent years, the pervading view is that firms must raise prices to survive. There is little scrutiny of whether firms are doing more than just surviving when they raise prices.

Finally, firms can raise prices because they know that consumers will keep buying. Weber and Wasner explain that “selling goods that people depend on” grants many firms extraordinary pricing power. Helpfully, the chief financial officer of Procter & Gamble has publicly boasted about this fact, stating that the company is ideally “positioned for dealing with an inflationary environment… starting with the portfolio that is focused on daily-use categories, health, hygiene, and cleaning, that are essential to the consumer versus discretionary categories which in these environments are the first ones to lose focus from the consumer.” Importantly, a significant proportion of Iran’s manufacturing base is devoted to household essentials. Meanwhile, Weber and Wasner point to government interventions during inflationary episodes as another reason why consumers put up with higher prices. Just like the stimulus checks that helped shore consumer spending during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, so too have cash transfers played a role in supporting household expenditures in Iran in the face of sanctions pressures.

Given that the same basic conditions for sellers’ inflation appear to exist in the US and Iran, it would be worthwhile to replicate the Weber and Wasner methodology to study the pricing power and profitability of Iranian companies. But even without a full study, a cursory review of the net margins of Iranian firms raises significant concerns that sanctions are increasing their pricing power of these firms and possibly even boosting their profitability. Comparing the net margins of companies listed in Iran’s securities exchanges (excluding financial firms) with inflation rates over the last decade reveals that, in general, profit margins rise in periods where inflation is elevated. In the four years leading up to March 2018, while Iran benefited from sanctions relief, the average profit margin for listed companies was 17 percent, while the average annual inflation rate was 11 percent. Since March 2018 and after Trump imposed “maximum pressure” sanctions on Iran, the average profit margin has risen to 26 percent. In the same period, annual inflation has averaged 40 percent. In short, Iranian companies appear to be more profitable on average when the country is under US secondary sanctions.

The continued profitability of Iranian firms has two ramifications for Western policymakers. First, it is a clear indication that elites in sanctioned economies can continue to accrue wealth, even as sanctions succeed in creating macroeconomic pressure. Second, if firms are in fact generating sellers’ inflation as part of their response to sanctions pressure, the economic resilience of firms is connected to the economic pain of households. Notably, Weber and Wasner raise the prospect that sellers’ inflation inevitably leads to “distributional conflict.” In their view, given that “living standards decline as real wages fall with rising prices,” labour will eventually push back on the profit maximisation by companies and demand higher wages. This too is a consideration highly relevant to Iran, which has seen an intensification of distributional conflict over the last decade. Protests over economic grievances have become more common, particularly protests over stagnant, delayed, or unpaid wages. Four consecutive years where inflation has exceeded 30 percent has eroded the living standard of Iranian households. In this context, firms may not be able to sustain their profit margins forever—in the medium-term, ever-rising prices will lead to demand destruction. However, while Weber and Wasner suggest that American firms have engineered a “a temporary transfer of income from labour to capital,” the implications for Iran, where firms have enjoyed increasing pricing power for the better part of a decade, are more dire.

The fact that Iranian firms have proven resilient under sanctions does have its benefits. This resilience has helped keep Iran’s economy from sliding into a deeper crisis. The resilience of businesses is also critical if Iran is to take advantage of any sanctions relief offered in a future diplomatic agreement. But the processes that underpin this resilience have significant distributional consequences. The sustained profitability of Iranian companies under sanctions represents an extraordinary and ongoing transfer of economic welfare from households to firms. In effect, not only are sanctions failing to weaken Iranian companies and their elite owners, but they are also hurting Iranian households profoundly. This suggests that the enhanced pricing power of Iranian firms and inflated corporate dividends are under-examined contributors to rising economic inequality in Iran, where the top income decile now controls nearly one-third of the country’s wealth. Sanctions were meant to make Iranian companies pay, but it is the Iranian people who are footing the bill.

Photo: IRNA

Ageing Energy Infrastructure is Holding Central Asia Back

Central Asia faces rising demand for energy, spurred by population growth and climate change, but most of the region’s power generation and transmission infrastructure dates to the Soviet era.

Blackouts and "rationalisation" of energy consumption (a euphemism for coordinated blackouts) are all too frequent in Central Asia. Energy shortages arising from limited generation, insufficient energy imports, or the poor state of the transmission network mean that blackouts recur. This winter, however, the situation grew significantly worse. Amid exceptional cold weather, many households, businesses, and schools remained without heating and electricity for days on end. Unusually, the blackouts not only afflicted communities in remote regions but also capital cities.

Most of the region’s inefficient power generation and transmission infrastructure dates to the Soviet era. Central Asia faces rising demand for energy, spurred by population growth and climate change. Steadily rising energy consumption has strained power grids. Demand from new types of consumers, such as cryptocurrencies miners, has also exacerbated recent crises.

At the same time that they face chronic energy shortages, Central Asian states must also significantly cut carbon emissions and accelerate the transition to clean energy—a challenging path, especially for Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, where domestic production of hydrocarbons secures the majority of domestic energy consumption.

Besides generation capacity, natural gas supplies and distribution present their own technical and political problems. Kazakhstan is the world’s ninth-largest exporter of coal and crude oil and twelfth largest exporter of natural gas; its total energy production covers more than twice its energy demand. Yet, it has not been able to reliably supply electricity within its own territory. In mid-January, Turkmenistan, despite sitting on one of the world's ten largest natural gas reserves, disrupted gas supplies to Uzbekistan for over a week due to technical problems. Last year, several regions of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan were hit by blackouts caused by a technical incident in the so-called “energy ring,” a Soviet-era grid connecting border regions of these three countries, including the Kyrgyz and Uzbek capitals and Kazakhstan’s largest city, Almaty.

Central Asian authorities and international stakeholders have acknowledged the urgent situation facing the energy sector. The existing infrastructure is being operated “well beyond its shelf-life,” and loses caused by inefficiency may reach around 20% in the electricity sector.

But addressing all these demand-side and supply-side challenges simultaneously is impossible; governments in the region will have to prioritize specific sub-areas of their energy sectors. In the meantime, they will need to grapple with new economic challenges arising in part from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The recent blackouts sparked considerable public anger given the financial impact, health risks, and general discomfort. Protests took place in several cities across Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. While these recent protests were small, the “Bloody January” protests in Kazakhstan and the Karakalpakstan protests in Uzbekistan point to the possibility that social and economic grievances can give rise to more significant unrest. Furthermore, many families relied on stoves to keep their homes warm, adding to the already high levels of pollution in Central Asia cities, resulting in further complains.

These extensive blackouts are also of concern to potential international investors. Without stable supplies of such basic utilities, investors will be deterred from Central Asia, leading to further economic stagnation. The ongoing crisis is a big test for Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and to a lesser extent Kyrgyzstan, three countries whose presidents have linked their political legitimacy with improving the economic and social conditions inside their country. To create jobs for their growing populations, these countries must grow their economies. But to grow their economies, the countries must boost energy production and significantly improve the distribution network. Securing the necessary financial resources for the extensive renovation of energy infrastructure is they key step for solving the energy shortages in the region. But securing new financing has become even harder because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has significantly added to the already significant risks of investing in Central Asia, resulting from power struggles and corruption within the ruling regimes.

This has not stopped Central Asian leaders from promising new injections of investment in energy generation and improvement of the existing grid. President Shavkat Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan announced a package of $1 billion to be invested in energy generation in the Tashkent region. But Mirziyoyev’s promise of new investment was clearly a political ploy, an effort to respond to public anger. The details of the investment and the expected economic, social, and political impact remain unclear. Governments in the region are luring new investors in the renewable energy sectors by setting ambitious targets. Kazakhstan aims to introduce new projects totaling 6.5 GW by 2035 and Uzbekistan plans to launch 7 GW of new capacity by 2030. However, many of these projections include nuclear power projects involving Russia’s Rosatom, which are now very unlikely to break ground.

Successful renovation of the energy sector at the national level also requires stronger political partnerships between countries given knock-on effects in the broader region. Tajikistan and Uzbekistan deliver electricity to Afghanistan, but domestic power outages in Uzbekistan briefly halted the export last month. Such disruptions in the national or regional grids are bound to reoccur and will add to the hardships faced by Afghans.

ADB predicts that demand will rise 30 percent across the entire CAREC region (which includes Central Asia, the Caucasus, Mongolia, and Pakistan). This means that no country has significant excess capacity it can share with its neighbors. The bank’s estimates put the cost of energy infrastructure modernisation for the region at between $136 billion to $339 billion by 2030. Upgrading transmission and distribution infrastructure alone is estimated to cost between $25 billion to $49 billion.

There are also other hidden costs. For example, the state usually subsidises electricity, gas, and coal, and any price increase brings a high risk of public dissatisfaction. Furthermore, there is a vast discrepancy in consumption between the winter seasons and the summer, which both generation and transmission infrastructure needs to reflect. The revenue potential of energy exports is deeply intertwined with the global economic situation. Hence, current estimates and political promises are bound to be revised sooner or later.

The recurring blackouts and subsequent deep freeze in Central Asia were caused by three decades of neglect, corruption, and poor planning. Any significant improvement in the situation would require years of persistent effort to overcome economic and political challenges. After the disruptions of the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, valuable time has been lost to begin the urgently needed modernisations of power plants and grids. For ordinary people in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan, the countdown to the next winter has already begun.

Photo: David Trilling

Iran's Special Relationship with China Beset by 'Special Issues'

This week, Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi flew to China for a three-day state visit at the invitation of Xi Jinping, marking the first full state visit by an Iranian president in two decades.

On February 14, Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi flew to China for a three-day state visit at the invitation of Xi Jinping, marking the first full state visit by an Iranian president in two decades. For Beijing, hosting Raisi was an attempt to regain Tehran’s trust after the significant controversy generated by the China-GCC joint statement issued following Xi’s visit to Riyadh in December. For Tehran, taking a large delegation to Beijing was an opportunity to remind the world that China and Iran enjoy a special relationship.

On the eve of the visit, Iran, a government newspaper, published a 120-page special issue of its economic insert entirely focused on China-Iran relations. Given the newspaper’s affiliation and the timing of the publication, the special issue is something like a white paper on the Raisi administration’s China policy and the perceived importance of a functional partnership with China.

The cover of the special issue speaks for itself—it calls for the creation of a triangular trade relationship between Iran, China, and Russia. Another headline declares that the Raisi administration is “reconstructing broken Iran-China ties.” In his pre-departure remarks, Raisi doubled down on this message, noting that Iran “has to pursue compensation for the dysfunction that existed up until now in its relations with China.” With this statement, Raisi both cast blame on Hassan Rouhani, his predecessor, for failing to maintain stronger ties with China, while also implying that China had let Iran down by failing to begin implementation of a 25-year Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement signed in 2021.

Iran’s grievances aside, the overall tone of the special issue is laudatory, suggesting that the Raisi administration has chosen to overlook China’s apparent endorsement of the UAE’s claim over the three contested Persian Gulf islands, which caused an uproar in Iran following the China-GCC consultations in December. But a development just before Raisi’s trip generated new controversy.

According to reports, Chinese oil major Sinopec has withdrawn from investing in the significant Yadavaran oil field located on the Iran-Iraq border. The Iranian government began negotiating with Sinopec in 2019 to develop the project's second phase. The negotiations were slow-going, in part because of the challenges created by US secondary sanctions.

Fereydoun Kurd Zanganeh, a senior official at the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), has denied the reports, claiming that negotiations with Sinpoec are ongoing. According to him, the Chinese energy company “has not yet announced in any way that it will not cooperate in the development of the Yadavaran field.” Whether or not Sinopec has actually withdrawn from Yadavaran, the slow pace of the negotiations and the difficulty for Chinese companies to deliver major projects—as in the case of Phase 11 of the South Pars gas field—reflect that China is an unreliable partner for Iran, at least while Iran remains under sanctions.

Nonetheless, the Raisi administration is keen to attract more Chinese investment. In an interview with ISNA published on January 28, Ali Fekri, a deputy economy minister, said that he “is not happy with the volume of the Chinese investment in Iran, as they have much greater capacity.” According Fekri, since the Raisi administration took office, the Chinese have invested $185 million in 25 projects, comprising of “21 industrial projects, two mining projects, one service project, and one agricultural project.” As indicated by the low dollar value relative to the number of investments, Chinese commitments have been limited to small and medium-sized projects. Beijing has mainly invested in projects that, according to Fekri, offer China the opportunity to import goods from Iran.

Comparative data shows Iran falling behind other countries in the race to attract Chinese investment. For instance, according to the data complied by the American Enterprise Institute, China committed $610 million in Iraq and a striking $5.5 billion in Saudi Arabia in 2022 alone. With secondary sanctions in place, the prospect of more Chinese investments in Iran is unrealistic.

Despite these obvious challenges, Iranian officials have been reluctant to admit that external factors are shaping China-Iran relations. Ahead of Raisi’s departure to China, Alireza Peyman Pak, the head of the Iran Trade Promotion Organization (ITPO), denied that Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia in December had precipitated a cooling of Beijing’s relations with Tehran.

“Such an interpretation is by no means correct. A country with an economy of $6 trillion naturally tries to develop its economy by working with all countries,” he said. Peyman Pak pointed to recent trade data to bolster his case. “In the past ten months, we have seen a 10 percent growth in exports to China compared to the same period last year,” he added, leaving out that the growth comes from a low base—China-Iran trade has languished since 2018.

In recent months, Peyman Pak has played a prominent role in brokering memorandums of understanding between Russian and Iranian companies—part of the push for a deeper Russia-Iran economic partnership. His participation in the delegation heading to China suggests that the Raisi administration is serious about shaping a triangular trade alliance between Tehran, Moscow, and Beijing. So far, that economic alliance exists only in the form of various non-binding agreements. China and Iran signed 20 agreements worth $10 billion during Raisi’s visit.

These agreements, like those before them, have a low chance of being implemented, especially while the future of the JCPOA remains in doubt. For now, China-Iran relations are limited to the text of white papers, memorandums, and statements. For his part, Xi offered Raisi some encouraging words. He reiterated China’s opposition to “external forces interfering in Iran’s internal affairs and undermining Iran’s security and stability” and promised to work with Iran on “issues involving each other’s core interests.” No doubt, the special relationship between China and Iran is beset by special issues.

Photo: IRNA

Iran Trade Mechanism INSTEX is Shutting Down

At the end of January, the board of Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) took the decision to liquidate the company.

At the end of January, the board of the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) took the decision to liquidate the company. Established in January 2019 by the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, INSTEX’s shareholders later came to include the governments of Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, Spain, Sweden, and Norway.

The state-owned company had a unique mission. It was created in response to the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018. European officials understood that the reimposition of US sanctions would impede European trade with Iran. The nuclear deal was a straightforward bargain. Iran had agreed to limits on its civilian nuclear programme in exchange for the economic benefits of sanctions relief. If European firms were unwilling or unable to trade with Iran, that basic quid-pro-quo would be undermined. For this reason, supporting trade with Iran was seen as a national security priority.

In August 2018, EU high representative Federica Mogherini and foreign ministers Jean-Yves Le Drian of France, Heiko Maas of Germany, and Jeremy Hunt of the United Kingdom, issued a joint statement in which they committed to preserve “effective financial channels with Iran, and the continuation of Iran’s export of oil and gas” in the face of the returning US sanctions. They pointed to a “European initiative to establish a special purpose vehicle” that would “enable continued sanctions lifting to reach Iran and allow for European exporters and importers to pursue legitimate trade.”

In November 2018, when the basic parameters of a special purpose vehicle were still being formulated by European officials, I co-authored the first public white paper explaining why establishing such a company made sense. Conversations with European and Iranian bankers and executives had made clear to me that trade intermediation methods were being widely used to get around the lack of adequate financial channels between Europe and Iran. If these methods could be packaged as a service by an entity backed by European governments, it would reassure European companies about remaining engaged in the Iranian market, while also reducing costs.

A few months later, INSTEX was founded. In the beginning, the company was run by the Iran desks at the EU and E3 foreign ministries. The officials tasked with working on INSTEX, who were often very junior, quickly realised they had little knowledge of the mechanics of EU-Iran trade. When they sought to enlist help from colleagues at finance ministries and central banks, they frequently met resistance. Many European technocrats were reluctant to support a project which had the overt aim of blunting US sanctions power, even at a time when figures such as French finance minister Bruno Le Maire and Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte were making bold statements about the need for European economic sovereignty. Even INSTEX’s inaugural managing director, Per Fischer, departed given concerns over his association with a company that had been maligned by American officials as a sanctions busting scheme. Then, in May 2019, when the Trump administration cancelled a set of sanctions waivers, European purchases of Iranian oil ended. That left INSTEX as Europe’s only gambit to preserve at least some of the economic benefits of the nuclear deal for Iran.

Later that year, INSTEX hired its first real team after a new group of European governments joined as shareholders and injected new capital into the company. For a time, things looked more promising. Under the newly appointed president, former German diplomat Michael Bock, a small group of talented individuals worked to define INSTEX’s mission and build a commercial case for the company’s operation. Their efforts led to INSTEX’s first transaction, which was completed in March 2020—the sale of around EUR 500,000 worth of blood treatment medication. The political pressure to provide Iran some gesture of tangible support during the pandemic had also greased the wheels in European governments.

But many considered the INSTEX project doomed even before the first transaction was completed. Certainly, Iranian officials were derisive of the special purpose vehicle. Given that Europe had failed to sustain its imports of Iranian oil and was unable to use INSTEX for that purpose, focusing instead on humanitarian trade, Iranian officials dismissed the effort, even after the feasibility of the special purpose vehicle was proven. That it took more than a year to process the first transaction also meant that the Europeans missed their chance to fill the vacuum caused by the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement. Without full cooperation from its Iranian counterpart, which was called the Special Trade and Finance Instrument (STFI), INSTEX could not reliably net the monies owed by European importers to Iranian exporters with those owed by Iranian exporters to European importers.

European officials will no doubt blame Iran for the fact that INSTEX failed, and it is true that the Iranian government never fully appreciated the political significance of European states taking concrete steps to counteract even the indirect effects of US sanctions. Of course, the decision to liquidate the company follows a spate of recent actions by the Iranian government—nuclear escalation, the sale of drones to Russia, and the brutal repression of protests—that make the continued operation of INSTEX politically untenable.

But most of the blame for INSTEX’s failure must lie with the Europeans—the company’s demise predates Iran’s recent transgressions. European officials promised a historic project to assert their economic sovereignty, but they never really committed to that undertaking. A mechanism intended to support billions of dollars in bilateral trade was provided paltry investment. European governments never figured out how to give INSTEX access to the euro liquidity needed to account for the fact that Europe runs a major trade surplus with Iran when oil sales are zeroed out. For the Iranians, this alone was the evidence that European leaders saw INSTEX as a political gesture that might placate Tehran, rather than an economic instrument that would bolster Iran’s economy in the face of Trump’s “maximum pressure.”

Paradoxically, Iran will lose nothing as the liquidators shut down INSTEX, quietly selling the few assets the company had accumulated—laptops, office chairs, and perhaps some nifty pens. It is Europe that is losing out. INSTEX was supposed to be a testbed for new ways of facilitating trade without relying on risk-averse banks to process cross border transactions. Successful innovation in this area would have given a new dimension to European economic diplomacy and helped Europe assert the power of the euro in global trade.

With the writing on wall, INSTEX’s management made one final attempt to give the company a future. Beginning in 2021, the company pursued a French banking license—a pivot that INSTEX’s board had approved on a provisional basis, but which was halted in early 2022. It is hard to overstate how significant it would have been had INSTEX emerged as a state-owned bank with a specific mandate to process payments on behalf of European companies that wish to work in high-risk jurisdictions, including those under broad US sanctions programme. Such a bank could have become a powerful tool for Europe to assert its economic might in the face of US sanctions. Moreover, it would even have been useful in cases where Europe is applying sanctions, like Russia. After all, a commitment to humanitarianism means that goods such as food and medicine must continue to be bought and sold even when most transactions with a given country are prohibited. INSTEX could have helped make European sanctions powers more targeted and more humane.

For a company that managed just one transaction, a surprising amount has been written about INSTEX. It has been the subject of news reports, think pieces, and academic articles. Even if many people struggled to understand what the special purpose vehicle aimed to do, its existence was novel and therefore noteworthy. For those insiders directly involved in the company’s saga, and for those of us who have closely followed from the outside, the main takeaway seems to be that there is much yet to be learned about the complex ways in which US sanctions impact European policy towards countries like Iran, through both political and economic vectors. In this respect, INSTEX did achieve something. A group of technocrats in European foreign ministries and finance ministries learned valuable lessons, often reluctantly and with great difficulty, about the limits of Europe’s economic sovereignty. Whether those lessons can be institutionalised remains to be seen. But a fuller post-mortem on INSTEX would no doubt offer important lessons for the future of European economic power in a world dominated by US sanctions. Learning those lessons would be its own special purpose.

Photo: Wikicommons

What Role Do Economic Conferences Play in Uzbekistan’s Development?

Uzbekistan is seeking a dialogue with the world and economic conference can serve to build trust and generate credibility.

Back in November, I travelled to Samarkand to attend the Uzbekistan Economic Forum. I had been to the ancient city nearly a dozen times, but this was my first professional event there. The Uzbekistan Economic Forum did not suddenly convince everyone that Uzbekistan is a special country. But it did show that Uzbekistan was becoming a more normal one.

Not everyone in Uzbekistan was happy with the conference. Some journalists and bloggers questioned why Uzbekistan’s government needed to convene yet another major and costly event. Others wondered if the return on investment would be worth it. Concerningly, the costs of the forum were not disclosed. Clearly, the organisers could have done a better job in publicly communicating the rationale for such a large event and why such conferences matter. To me, there are three reasons why they do.

First, Uzbekistan needs to foster regular dialogue with businesses partners, investors, and lenders who are independent from the government. Such actors are accountable to their shareholders, are subject to intense international media scrutiny, and must follow varied regulations around governance and sustainibility. Therefore, they can audit Uzbekistan’s achievements and shortcomings more honestly, generating important information for local media and civil society.

A country whose debt burden is equal to 40 percent of its economic output must be open to scrutiny of its economic policies and institutions. The forum’s thoughtful programme presented the opportunity for such scrutiny, with topics ranging from political reforms to economic inclusivity. The organizers brought in people who could ask tough questions (including former CNN and Bloomberg journalists) as chairpersons for the panel discussions. Senior representatives from the IMF, IFC, World Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure and Investments Bank, regional central bankers, financiers, investors, and many consultants featured on these panels.

There was a time when frankness came at a cost. In May 2003, panelists from the EBRD, which was leading Uzbekistan through its protracted post-communist transition, spoke truthfully about the country’s economic and political shortcomings at the Annual Meeting in Tashkent. By 2005, EBRD war hardly making any loans in Uzbekistan and by 2007 it had exited the country altogether, unable to operate in an environment in which the authorities demanded deference. It was not until a decade later that EBRD returned to Uzbekistan. Today, the bank has 65 active projects with over EUR 2 billion in total portfolio value. With that much at stake, it is reasonable to expect that the EBRD and peer institutions will continue to speak up, especially as its activists continue to push the bank to live-up to its pro-democracy mandate.

Second, Uzbekistan needs a platform to prove its bureaucratic capacity, as it seeks to stay the course of increasingly difficult structural reforms. In contrast to heavily protocolled political events with predetermined outcomes such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or Inter-Parliamentary Assembly, participants of economic forums in Uzbekistan are more demanding, represent diverse stakeholders, and care about performance dynamics. The newly formed Ministry of Economy and Finance, the Ministry of Labor and Poverty Reduction, and the Ministry of Justice—which oversee social policy—face new challenges every day. The nominally independent Central Bank and the judiciary are undergoing significant changes with unclear outcomes. They will all need to prove that they can uphold Uzbekistan’s domestic and international commitments and pay the bills.

At the same time, reform-minded public administrators themselves need businesses, civil society groups, and international professionals to get their president's attention in the highly centralized system. In Uzbekistan, the presidential administration can be reactive, prioritizing issues in response to media coverage, expert commentary, formal reports, and face-to-face meetings. It is no secret that certain business leaders may enjoy better access to the president that many ministers do not have. So, it is good when investors are both long-term thinkers and legally bound to seek clean deals. These investors and reform-minded public administrators can form coalitions as part of two-level game through which domestic reformers in transition economies find the means with which to amplify their voices.

Alongside many countries “stuck in transition,” the Uzbek government continues to face challenges outlined by the IMF in its 2014 review marking 25 years after the end of communism in Europe. Uzbekistan needs to reign in its exorbitant public expenditures, improve the business climate, enable market competition, enforce state divestment, and ensure rule of law. It was reassuring that almost all keynote speakers in Samarkand said the same. By the end of the first day (most discussions can be watched freely online), it was clear that there was broad consensus about what needs to happen to enable prosperity.

The Uzbek ministers and senior officials speaking at the conference shared this consensus and acknowledged problems. Some even joked, earning sincere laughter from the diverse audience. Importantly, the conference was held in Uzbek and English — this was more than political symbolism. Russia’s war on Ukraine has had varied effects on the Uzbek economy. These have been mostly negative (e.g. reduced financial inflows and increased social policy burden), though there have been a few silver linings (e.g. capital relocation, higher commodity prices, and parallel exports). After independence, Uzbekistan, like other post-Soviet states, pursued legislative and regulatory harmonisation with Moscow. But the country’s bureaucracy is starting to look beyond Russia. The use of the Uzbek language helps the central government connect to a wider swath of society. The use of English, meanwhile, represents a search for a wider cooperation with foreign countries.

Finally, these conferences help set expectations—and there are many expectations being set. That Uzbekistan will privatise the promised 1,000 more state-owned enterprises. That utility and energy prices will be liberalized. That the economic growth will be increasingly supported by foreign direct investment rather than direct borrowing. That more will be done to empower and separate the judiciary from the executive branches. That the Oliy Majlis, Uzbekistan’s legislature, will pass new competition law and that it will be signed. That Uzbek GDP will rise to USD 100 billion by 2026 and USD 160 billion by 2030. That the country embraces a free market economy, trusting that its people can achieve more with less state intervention. Whether Uzbekistan meets these high expectations is something that can be assessed when it is time to gather for another forum.

Uzbekistan is seeking a dialogue with the world. We can quibble about the optics of such conferences, but they do serve to build trust and generate credibility. There was a time when economic conferences in Uzbekistan had long titles, glorified the present, and discussed the future in only abstract terms. Back then, the desired outcome was applause—those conferences played no role in the country’s economic development. In Samarkand, a different kind of conference took place.

Photo: Uzbekistan Economic Forum

How Shifts on Instagram Drove Iran's 'Mahsa Moment'

Iranians are using Instagram for political activism like never before. But these changes were not sudden. The “Mahsa Moment” was driven by user trends on social media that have been years in the making.

This article was originally published in Persian.

In a narrative crafted by various political and intellectual currents, the “Iranian Instagram” is often presented as a means of depoliticising the attitudes and behaviours of the Iranian people, with its users engaging in vulgar content, falling for false news and claims, cursing at famous figures, and morbidly posting accounts of the more attractive sides of their daily lives. This same formulation is used by the conservative movement (also called the Principalists movement) to realise their policy of "organisation" and "protection" of the Internet. Using comparable language, pro-change political currents also direct users to ostensibly more political platforms, such as Twitter and Clubhouse. However, if this is the case, why has Instagram become one of the most prominent platforms for expressing and even organising political protests in the “Mahsa Moment?”

The simplest and shortest response to this question is to attribute everything that has occurred over the past two to three months to the Islamic Republic's enemies. This response has been heard repeatedly on official domestic media in recent months. Some of the self-proclaimed leaders of the people's protests in the media outside of Iran have given the same answer in different words, claiming that these events are the result of their years of hard work and meticulous planning. This type of analysis of people's collective actions is not only unenlightening and ineffectual but is a significant contributor to the current crisis.

However, another approach might be to temporarily set aside preconceived notions about online social networks in favour of a more empirically grounded and scientifically sound approach to answering this question. A portion of the answer to this question can be found by analysing the changing trends on Iranian Instagram.

Those of you who have been following along for the past three years may recall that I began a longitudinal study of Iranian Instagram in 2019 and have since published an analytical update three times in the early fall of 2019, 2020, and 2021. This year, data collection and analysis took longer than usual due to Internet filtering and interruptions, delaying the report preparation for the fourth phase of this research.

With these explanations, the findings of the fourth consecutive year of this research will be presented within the context of the question posed at the beginning of the report. The findings of this study demonstrate that the transformation of the Iranian Instagram space at the “Mahsa Moment” into a platform for online protests and the organisation of offline protests cannot be attributed to a pre-planned project. Rather, we must understand and analyse this phenomenon in light of the agency of users and the gradual changes that have occurred on Instagram in Iran over the past few years. In addition, despite tightening restrictions over the past year, Iranian Instagram continues on its path, both quantitatively and qualitatively, consistent with the previously optimistic changes.

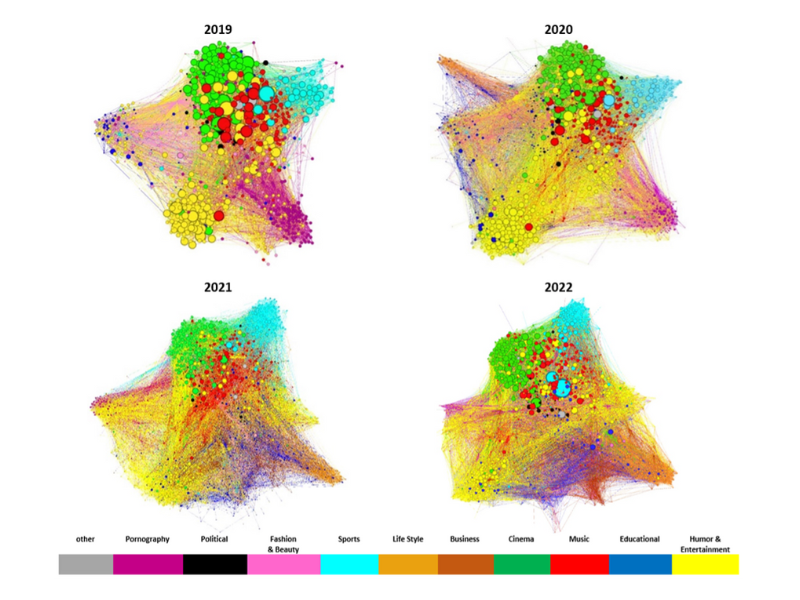

Figure 1 depicts the frequency of active popular Iranian Instagram pages between 2019 and 2022. Despite the tightening of various restrictions facing Iranian users on Instagram, the number of active Iranian pages on Instagram with more than 500,000 followers increased by 17% in 2022, reaching 2,654.

Figure 1: Frequency of active Iranian Instagram pages with over 500k followers from 2019 to 2022

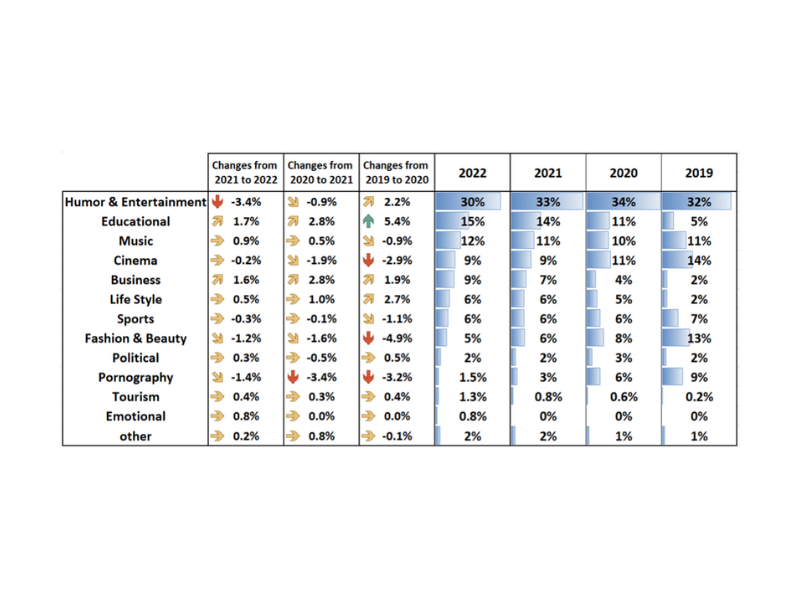

As displayed in Table 1, the share of "humour and entertainment", "fashion and beauty", and "pornography" pages among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages has decreased significantly over the past year. While the decline in "fashion and beauty" and "pornography" pages continues a longer trend, the declining ratio of "humour and entertainment" pages on Iranian Instagram over the past year is something new. In contrast, the percentage of "educational" and "business" Instagram pages has continued to rise in 2022.

The appearance of "tourism" and "emotional" pages on popular Iranian Instagram pages in 2022 is another notable change. On the tourism pages, content pertaining to tourism in various regions of Iran and the world is published, whereas, on the emotional pages, content that represents human feelings and emotions are published.

Table 1: Share of popular pages by primary subject from 2019 to 2022

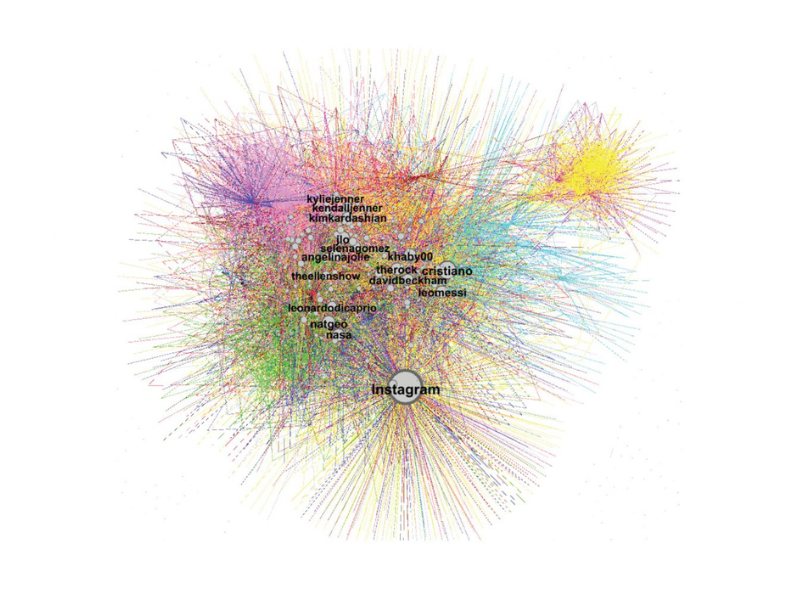

The trend of changes in the network of relationships between popular Iranian Instagram pages is illustrated in Figure 2 using the Indegree Index. When comparing the changing trend of the graphs from 2019 to 2022, we observe that education (dark blue), business (brown), lifestyle (orange), and fashion and beauty (pink) pages have become increasingly integrated within their respective fields and have distanced themselves from other fields. In the upper portion of the graphs, from 2019 to 2022, we notice an increase in the intertwining of sports screens (pale blue), movies (green), and music (red). In other words, these three types of popular accounts—also known as "celebrity” accounts—have gradually shaped a field that is related to issues outside of their profession. In this multifaceted field, in addition to celebrity pages, there are humour, entertainment, political, and social pages (yellow, black, and grey).

Figure 2: Changes in the network of relationships between popular Iranian Instagram pages from 2019 to 2022, as measured by the Indegree Index

Figure 3 displays the ten Iranian Instagram influencers with the highest authority based on the Authority index. All of these individuals belong to one of the three categories: sports, film, or music. These three categories also overlap. Moreover, with the exception of two individuals, the rest post additional content on the page related to their audience's political, economic, and social concerns and demands, as well as their profession and area of expertise. Let us refer to this type of celebrity as a "celebrity-activist.”

By a significant margin, Ali Karimi has the highest authority among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages, followed by Ali Daei, Golshifteh Farahani, Javad Ezzati, Amir Jafari, Bahram Afshari, Mahnaz Afshar, Majid Salehi, Parviz Parastui, and Reza Sadeghi.

Figure 3: Network relations between popular Iranian Instagram pages in 2022, as per the Authority Index

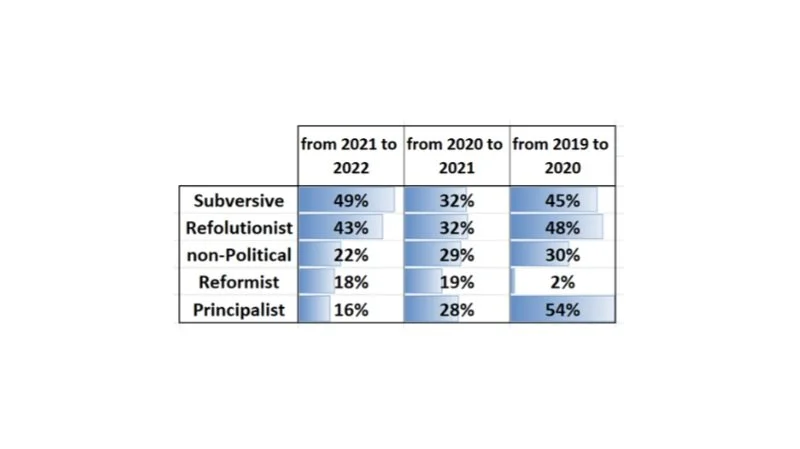

By reflecting on Table 2 and reviewing Table 1, we can gain a greater appreciation for the reasons why celebrity-activists on Iranian Instagram gain authority. Table 2 demonstrates that the number of followers of popular subversive pages has increased by 49% over the past year. This index was 43% for refolutionist (neither revolutionist nor reformist), 22% for non-politicals, 18% for reformists, and 16% for conservatives (Principalists). Comparing these statistics to those from previous years reveals that the notion of protesting the current political situation has become increasingly popular and a sought-after item on Iranian Instagram over the past year.

In contrast, as shown in Table 1, the proportion of political pages (individuals, groups, or organisations professionally engaged in political activity) among the most popular Iranian Instagram pages did not change significantly between 2019 and 2022, fluctuating by approximately 2%. In other words, Iranian political professionals of various political orientations lack the capacity and acceptance to represent the nation's political attitudes and demands. Iranian Instagram users have increased pressure on other popular Iranian Instagram pages, requesting that they reflect and even represent the political protests of the Iranian people. As previously explained, education, business, lifestyle, and fashion and beauty pages have not directly engaged with this demand of users due to professional considerations; however, a substantial portion of the movie, sports, and music pages have responded positively to the demand of their followers, largely due to their professional considerations. In actuality, it is the crisis of political representation that has placed celebrities in the position of representing the political demands of the Iranian people and given rise to the phenomenon of "celebrity-activists.”

In this sense, these are the people who have agency and have utilised the smallest opportunities to protest the status quo. In this way, they also take advantage of the opportunities provided by celebrities. In such a scenario, political professionals dissatisfied with the formation of these relationships between users and celebrities alter the truth and promote the narrative that "these excited people" have been duped by "illiterate celebrities!" Almost every political faction has employed such insults on occasion. Of course, these same "illiterate celebrities,” once defended participating in elections and voting for reformists, thereby increasing voter turnout. But, at the current time when celebrities are under the pressure of users and the online space has aligned with the Mahsa movement, conservatives and a significant portion of reformers assert that "the excited people" have been duped by the celebrities they follow. In actuality, instead of taking fundamental and principled measures to address the escalating crisis of political representation, political professionals sometimes align themselves with "concerned artists and athletes" and "intelligent people" and sometimes curse "illiterate celebrities" and "excited people" in accordance with their immediate interests.

Table 2: The rise in followers of popular Iranian Instagram pages by political orientation from 2019 to 2022